For awhile now, I’ve been thinking about the need for drawing a distinction between ‘escapist’ fiction and what is merely called escapist fiction. This is, in some ways, related to the unbelievably old and dead horse about genre fiction vs. literary fiction, but I think goes beyond that. The term ‘escapist’ is usually given employment as a pejorative to fiction deviating in some way from material reality (often but not always genre fiction), and thus, from literary realism. The line is that these kinds of fiction do not engage with reality and its constitutive material and social conditions, but rather retreat into a stuffy, hermetic den. This is still a claim I want to take seriously, however. The fiction of the fantastic in the majority of its 20th and 21st century manifestations has been, for a significant period of time, synonymous with shying away from an engagement with the world, as if all speculative fiction were guilty of what Athena Andreadis calls “persistent neotony.”

All I will say about this decrepit chestnut is that, given the subsumption of ‘magical realism’ into literary fiction, all reservations about escapism can be seen to pivot on refuting a reverse of the sort of argument Abraham made to God in the Old Testament, suggesting that Sodom be spared from destruction if “fifty righteous” individuals be found. The number dwindles to forty-five, then forty, etc, with each repetition of the argument, and God hedges each time. The traditional gripe with non-realist fiction boils down in this way to an argument based on the ever diminishing returns of an ambiguous ‘realism’. What if there is only one psychologically acute specter of a dead grandmother? How about two banshees? Three sentient, nitrogen based creatures living in deep sea black smokers? The only way out of this Abraham-argument is to draw arbitrary lines in the sand, and cling to an increasingly flimsy and irrational realism.

That clear, what can the fiction of the fantastic tell us about current conditions? It is tempting to end the question with “…that realism can’t?” But this suggests to me a draconian politics of narrative, wherein the fantastic must be able to identify itself at all times for when Sheriff Joe rolls around, must marry a neighboring, tepid, middle-class realist romance to obtain a green card. And in knee-jerk reaction to this I would like to say that the fantastic should be able to exist in a story for no reason at all. Yet at the same time, in the words of a contemporary weird-writer whose name I have forgotten, “the story is the telling.” And if the fantastic is to remain vital, to be dynamic, surely it must do something.

What it does, and what it can do, brings us to the question of escapism. Let us assume the old claims are correct; the fantastic is synonymous with the escapist. Rather than construct a hard and fast, false-opposition between an illegitimate escapism and a legitimate escapism, it’s probably better to work around a more fluid conception that posits two basic “types” of escapism which fantastic fiction can move back and forth between in various degrees.

In fiction in general, there is a particular injunction to “write as it is,” where you reproduce without flinching the awfulness and loveliness of your particular moment in culture and space-time. An alternative injunction often proposed is that one should “write how it should be,” or “write how it should not be, but might.” The second injunction says that the mere reproduction of things as they are takes an active part in their reconstitution, that the army of literary Frankensteins keep this or that monster alive by writing it so many times. As the previously-mentioned-on-this-blog Junot Diaz, says: “It’s our fiction where the toxic virus of racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, etc. passes from one generation to the next, and the average artist will kill you before they remove those poisons.”

Along this line, as an addition to the old law about science fiction technology becoming reality if written often enough, one could add: The current order of things will remain the current order if written often enough. The original law refers to positive extrapolations of technology; the latter to a politics of status quo neither positive or negative. The first is “hard,” the second “soft,” if you will. Yet both operate in a similar way.

I want to apply the first injunction to the realm of fantastic fiction on the level of escapism. This type of escapist work is, to glean puerilely from Adorno, where “the dream has no dream.” By writing (often unconsciously) “as it is,” this mode’s fantasies and deviations from reality are actually reproductions of it. Its speculative societies are replications of actual ones, its grasping for difference reaches only sameness dressed in artifice. Its otherness and its difference are shams for the status quo and normality. Its escape is only a return to the current state of things, with or without critique or analysis. Its escape is almost an escape from the fantastic itself. It provides familiar comfort but with a sheen of the strange. This type of work at its extreme is what Barthes talked about in Mythologies with Jules Verne’s novels being about the bourgeois subject who, “re-invents the world, fills it, closes it, shuts himself up in it, and crowns this encyclopaedic effort with the bourgeois posture of appropriation: slippers, pipe and fireside, while outside the storm, that is, the infinite, rages in vain.” The veneer of the unusual is conquered by the comfortable (for the middle-class) status quo.

The escapist element of work done in this mode is often performed unconsciously, with ideology, as it were, leaking onto the page like a raw egg. Writers who work in this mode usually are not aware that they do. Those that are aware are usually attempting trenchant critique via reproduction (holding the mirror), which may not be the greatest use of the speculative’s potential to begin with, and in a basic sense is still replicating the current order, although possibly with the added tinge of romance much fantastic fiction has, however dystopic. Unflattering and gritty portrayals have, in a sense, been co-opted and given their own noir-ifying appeal, whether in “grimdark” genre-fantasy or whatever. The current order becomes a meaningless noir stage-set, like generic dark bars and shadowy figures smoking cigarettes. The critique tends to de-claw itself. The status quo in all its resplendent shittiness becomes normalized. (Unforgiven, the Western that tried to de-mythologize the old Hollywood West, is the new mythology.)

An example of the other type of escapism, of “writing as it should be”, would then be like Leonora Carrington’s novel The Hearing Trumpet, in which a group of ninety year old women overthrow Christian patriarchy and establish a magical, paganist matriarchy. It is a different mode of escapism because it at least succeeds in presenting a different vision of life, and one in which the state of things are changed irremediably. Any speculative fiction presenting an actual alternative to its particular moment is working in this mode. This strikes me as a more useful and fruitful mode in a politically lethargic time, and on a basic level. When the present is viewed as immutable and permanent, it is more effective than ever to merely present something different, to show the dream in possession of a dream. Also along this line is Delany’s novel Stars in My Pocket like Grains of Sand, which is thematically all about diplomatic navigation and desire as a means of negotiating and navigating difference.

For breaking up cultural and political lassitude, this latter mode seems to have the most potential for fantastic, speculative fiction going forward. It seems to me the most promising work possible for science fiction and fantasy, of presenting alternatives to the present, rather than stylistically reconfigured presents with analogues of the Isreal/Palestine confict and rapacious capitalist world-systems eradicating their planets of resources, and so on. Genre fantasy can also do this. But what about horror?

Horror does not generally exist or function on the same sociologically focused level its two siblings do, so what can it tell us about what it is to live today under our particular set of conditions? Isn’t the feeling of terror a primitive, early-human condition? Given that so many of our cultural ills and prejudices, our historical tragedies and errors, live on as ghosts, maybe it is not so far-fetched for it to speak to us in a relevant way. But I want to interrogate this further, later on.

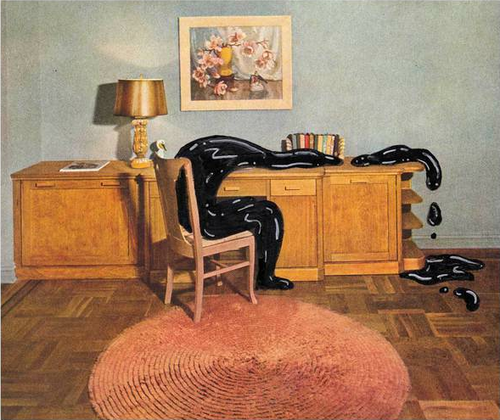

(Image is a speculative theater design by Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin. I chose this as much for its relevance to this post’s feckless dribblings as for its ambiguity. The theater design displays an obvious and radical divergence from traditional theater design – the stage is outside, whereas the seating is inside. The stage is, apparently, the street of a city. Is this radical change in design realism taken to its extremity, as in, saying to the audience, “You want verisimilitude? Here, look out on the fucking street outside, with a dog and some rain and shit. Pretty real, isn’t it?” Yet the street-stage may not actually be a street, it could actually be a more traditional extension of the theater itself, being nothing more than an elaborately constructed stage which happens to include a fake street, fake rain, a dog which may or may not be real, and relatively small motions towards a city that contains them all. We do not even know if the street-stage which the audience looks out upon has any relation to the physical location of the theater itself. Is this a stage-as-portal? Is it the same city, or is it a speculative one, a city that should or should not be?)