I’ve just read Wakefield Press’ new Gabrielle Wittkop releases, the novel Murder Most Serene, and the untimely-death-themed novella collection Exemplary Departures. The first thing one notices about them is how beautiful their design is. Both feature the art work of Nicole Duennebier, and whoever worked on the design for Murder uncorked one of the loveliest covers I’ve ever seen. I prefer her earlier novel The Necrophiliac to Murder Most Serene, but it is a worthy read for reasons I will get into shortly. Exemplary Departures is a work that should be of great interest to readers of the macabre, the fantastique, the surreal, and the supernatural, although in a literal sense it only belongs to the first. Wittkop is a writer whose work can (reductively but profitably) be taken as an alliance of the Marquis de Sade and E.T.A. Hoffman, both of whom figure in epigraphs and footnotes to the two books. Before I get into the texts, though, something of a preface:

I’ve just read Wakefield Press’ new Gabrielle Wittkop releases, the novel Murder Most Serene, and the untimely-death-themed novella collection Exemplary Departures. The first thing one notices about them is how beautiful their design is. Both feature the art work of Nicole Duennebier, and whoever worked on the design for Murder uncorked one of the loveliest covers I’ve ever seen. I prefer her earlier novel The Necrophiliac to Murder Most Serene, but it is a worthy read for reasons I will get into shortly. Exemplary Departures is a work that should be of great interest to readers of the macabre, the fantastique, the surreal, and the supernatural, although in a literal sense it only belongs to the first. Wittkop is a writer whose work can (reductively but profitably) be taken as an alliance of the Marquis de Sade and E.T.A. Hoffman, both of whom figure in epigraphs and footnotes to the two books. Before I get into the texts, though, something of a preface:

A while ago I read a book of literary criticism by Annie Dillard, Living by Fiction. In her book, there is something she identifies as the “writerly surface,” and then another level below it, a substrate of signification pulsating beneath the sentence. The surface is similes, metaphors and analogies, the craft of phrase-making, turning an ear to the work of finding pleasing sounds like a pig to truffles, allusion, and the invention of striking imagery. The substrate below the sentence is filled with plot, theme, allegory, sense of timing, the generation of meaning and its themes, characterization; in short, the general deep structures found in any work, the elements of a text which do not appear in the literal word by word, sentence by sentence surface. These are elements that only appear, so to speak, when you stand a ways off to get a proper look at them. A dull surface can hide great power, just as a shining surface can hide its deficit.

In this same work by Dillard, she mentions how modernist writers live on the surface, and turn their characters into what she derisively calls “figures”. Characters become objects adorned with unusual facts. She singles out Gabriel Garcia Marquez as an instance of this, saying that though his characters walk on water, are ghosts, absorb themselves into stained glass on holy days, or wear necklaces of parsnips, they do not elicit any sympathy. They are not characters, but objects, emotionless figures, pieces of setting given names. The reader does not relate to them, but simply gawks at them like novelties or admires them like landscapes; picturesque valleys that lift up their skirts and shuffle around for our amusement. She calls this method of fobbing off character and narrative at the expense of imagery “surface flatness,” an emigre term originally from the plastic arts.

On this note, in her novella, Murder Most Serene, Gabrielle Wittkop’s narrator compares herself to a bunraku puppeteer (kagezukai) and openly refers to her characters as “figures”. MMS has a threadbare historical mystery scaffolding, concerning the deaths by poison of the various wives of Count Alvise Lanzi in the Republic of Venice. Yet it basically unfolds as a procession of images going by, and even the plot, with its succession of wives dying of poison, suggests a processional ritual, a merry dance macabre. Wittkop keeps nothing secret about this, even saying through her bunraku narrator, “Syllogistic conclusions being fundamentally devoid of interest, however, their premises and their ornamental setting alone shall be our entertainment.” With this admission of her opinion that mystery tales are fucking boring, the reader is given a tale of poisonings, familial greed, clerical hypocrisy, and most of all, the 18th century city of Venice itself, the city “whose mirrors drink the dark.” In a passage characteristic of her prose, and also quoted in full by translator Louise LaLaurie for her introduction, Wittkop renders foggy, waterlogged Venice:

A city that shows only one-half of herself, held aloft on millions of felled trees, upon the forests of Istria, the great trunks cut down, dragged, floated, flayed, and sawn into piles, planted in the mud, bolt upright and tarred like mummies, chain-bound oaks, hooped in iron, held motionless in the sand for all the ages, doubly dead, etiolated corpses encrusted with lime, dead mussels, putrefied seaweed, swathed in nameless debris, decomposed rags and bones. A twin city beneath the city, inverse replica of its palaces and domes, its canals metamorphosed into the skies of Hades, a response but not a reflection, for this is the city of darkness, the city whose skies are forever black, the city below, on the other side.

In MMS, abbots have “pederastic noses”; beautiful vestments hide sores; poison produces incandescent glowing in the gut, released only by graphic, stomach-bursting explosions in stuffy drawing rooms; everyone plays the game of power, and mostly everyone loses; destitute, elderly tumblers ply their acrobatic skills on waterfronts and are pelted and assaulted; Giacomo Casanova, in between venereal play with noble ladies, frightens the city with false rumors of earthquakes; the rich hide themselves away in miniature, island-bound mansions eating moleche and chewing on the scraps of rumor; the canals are filled with corpses like noses with boogers. (The several sarcasms in the last sentence should make clear that sometimes the repetition of things decayed and rotting becomes ridiculous, but the camp is intentional, I think.) Wittkop states in her preface that her evocation of the city comes from the artworks of Pietro Longhi and Giovanni Tiepolo, but with the sardonic fixation of her images, it is clear we are just as much seeing the influence of Sade.

It is an enjoyable work, lightweight even, and much of it is just the detatched kagezukai observing for us the agonizing deaths of various women in various poorly heated rooms. Occasionally there is a scenic tour of Venice’s pools of urine, or its perennial forms of bread and circus, such as a carnival that lasts five months. There is no emotional development of the characters, and the mystery plot, true to form, ends up being predictable and “fundamentally devoid of interest.” Nonetheless, her prose is a pleasure.

Having mentioned “the divine Marquis” and Hoffman, it is also appropriate to mention the influence of Poe, a not astonishing connection given the Southerner’s influence on French literature, as well as his appearance as a character in Exemplary Departures. I will quote Baudelaire here, by way of Arthur Symons, and leave it to speak for itself: “Like our Delacroix, who has elevated art to the height of poetry, Poe loves to move his figures upon a ground of green or violet where the phosphorescence of putrefaction (as in The Case of M. Valdemar) and the odour of the hurricane, reveal themselves.”

The stronger of these two releases, Exemplary Departures does not possess the same surface flatness that bedevils Dillard and quickly loses my interest. Three of the novellas are excellent, “Idalia on the Tower,” “Baltimore Nights,” and “A Descent.” The remaining two that begin and close the collection (“Mr. T’s Last Secrets” and “Claude and Hippolyte”) are much weaker although lovingly written. It is appropriate to pair “Nights” and “Descent” together, as both detail descents into the underworld in some sense. “Nights” is Wittkop’s speculative reconstruction of Edgar Allan Poe’s last days before he died at Washington College Hospital in Baltimore; “Descent” depicts the downfall of a pathetic man, Seymour M. Kenneth, (a name that gives off strong Tom Disch vibes to me) and his eventual demise in a fetid hole below Grand Central Station.

Poe, in “Nights,” is flustered and harried by his constantly disappearing suitcase full of manuscripts. Unseen rivals are out to get him, and they have spies in every sliver of shadow: “They were plebeians. They smelled of cheese.” Wittkop’s Poe is a delusional man wending towards his own death, visited by angels, often feeling as if he could “vomit up his own heart,” but still clinging to his aristocratic pretensions, still capable of stunning speech. Not once is Poe named in “Nights,” but for someone even vaguely familiar with his history, everything is there: West Point, “Eureka,” theatrical parents, dead wife, his stormy relation with his stepfather, fascination with explorers, etc.

Wittkop keeps the textual fireworks of his delusions to a minimum until the very end, but gives the tale quiet moments of the uncanny, even in a very simple occurrence when Poe returns home from aimless wandering in town: “It was evening before he got back to his room, without having eaten anything. As soon as he’d lit the candle he looked under the bed and saw that the suitcase was gone.” In the context of Poe’s world, these two lines carry much greater weight than they do reading them ripped from their environs. Far from surface flattening, the literary contours of “Nights” are taut and sinewy. As an example of perfect placement and timing, the subterranean invisible work of writing, there you have it.

“Nights” is a magisterial piece of historical fiction in addition to a depiction of a mind’s descent into lurid hallucination. Take as example this wonderful little figurine from near the end, a piece showcasing both Wittkop’s research muscles and psychological acuity: “He climbed back into his carriage. Josef W. Walker bade him farewell gravely, and as he lifted his hat its tattered lining slipped out in a grotesque way, which Doctor Snodgrass gentlemanly ignored.” Baltimore is wonderfully evoked in all its late-Victorian grease, but without the awful steam-punk romanticism and object-fetishism (gaslights!) so often given to the period by contemporary writers. More importantly, unlike in Murder Most Serene, the conjuration of a time period is given something solid to hang onto, instead of just blowing ineffectually in the wind of words. I would compare it to and rank it in quality alongside Angela Carter’s incredible “The Fall River Axe Murders.” (It is also worth mentioning that Wittkop’s love of splattered entrails, black vomit, and rotting organic matter is tempered to fit the tale).

One more quote. Poe delves into a memory from his youth, the possible genesis for his writing of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym: “He remembered the nights when the old sailor, being eaten away like a pumpkin by pthisis, described for him the splendor and horrors of the seven seas, all the marvels that burst forth at the screech of the huge white gulls.”

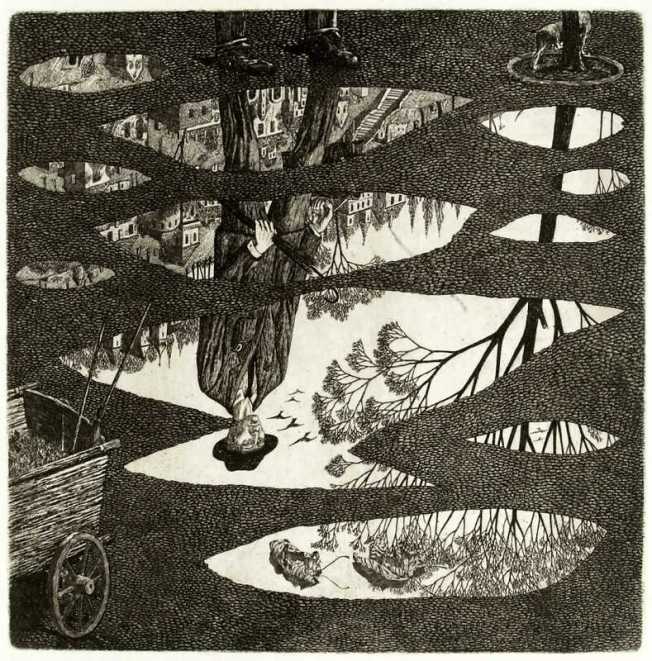

Felix Buhot, Winter Morning on the Quai de l’Hotel Dieu. 1876.

“A Descent” might be even better. After reading two 19th century fictions in “Baltimore Nights” and “Idalia on the Tower,” I did not expect to enjoy a tale set in contemporary times. It sounded jarring for a second, to read Wittkop without drays and steamers and tuberculosis. But the tale is quickly immersive, and if her Sadean side is muted in “Nights,” it comes out cackling in “Descent.” Seymour Kenneth is a wonderfully helpless character, an immature mediocrity overly attached to his mother, socially inept, and without skills or much in the way of intelligence. His mother dies and the sale of her unsuccessful cafe barely covers the cost of their debts, so Seymour strikes out into the world for the first time as a 30+ year old man. He ends up in a relationship with a woman named Emily Gordons, who just by coincidence happens to have a liking for weak, gutless men. He becomes the sub to her dom, working for no wages in her clothing retail store and referring to her at all times as “Mammily.” Somehow Seymour blunders his way into an affair with another woman that is as tepid as tapioca – an affair sordid in its lifelessness, practically kinky in its banal mundanity – and when Mammily finds out, it’s quits. It’s a shame Seymour was not receiving any pay during those years, because now he is 45 and has no job experience and no cash. To New York he goes, and his ultimate departure, exemplary in its own way.

Continuing the faint Tom Disch vibe I get from this tale, I’m reminded of Chip Delany’s comment about how Disch was brilliant at portraying the inner thoughts of stupid people. Wittkop is quite the hand at this too, it turns out, and when she graces us with Seymour’s thoughts the results are convincing and amusing. Seymour, on fleeing to New York, gets the bright idea of driving after entombing himself with whiskey: “Before him, the livid road ran on like a madwoman, running ahead reluctantly, while he gave chase to the beam of his own headlights.” The not at all shocking outcome of this is that Seymour kills a pedestrian, so he continues driving to the city and abandons the car on the outskirts. He settles down at a flophouse and from there his descent only increases in its velocity, culminating in his setting up shop in a corner of the humid underground heating system below New York’s train terminals. Perhaps it’s the contemporary setting, perhaps it’s the indifferent brutality and stupidity of its characters, or simply the meticulous rendering of its ghoulish settings, but “Descent” has the most visceral and immediate impact of any tale in Departures. As always with Wittkop, the allusions are there: Hoffman’s mines of Falun, Sarpedon, Hypnos, and Thanatos.

“Idalia on the Tower” is a strong piece set in the German Rhineland, with references to Alfred Kubin and plentiful period details; “Claude and Hippolyte, or the Inadmissible Tale of the Turquoise Fire” is also rather good, but not to the level of “Idalia” or the others, though it has its charms. “Mr. T’s Last Secrets” I found a little thick on her occasionally purple descriptions and the inscrutable character of Mr. T left me cold. This may well change on re-readings, but with two really excellent pieces of fiction, and a few solid others, Exemplary Departures gets my recommendation.