“Now I could eat a piano, shoot a table, inhale a staircase. All the extremities of my body have orifices out of which come the skeletons of the piano…” – Gherasim Luca, The Passive Vampire.

* * *

I have grown up from the rubbish tips that line the town. I have two dripping piss-holes for eyes and a tail that drags along behind me, sucking filth from the earth and pushing it upwards towards my head, and gathering it there, so that it grows bigger and bigger, fouler and fouler. My tail is made from fish-bones and aluminum tins and the scum that accretes around drains. I hold up my head with my right arm, which is bigger than the left. I leave the left to hold my cane, which is just the post removed from a stop sign. My legs are always in motion, even when they are still.

I like to stagger along behind the fences of yards at night, so that anyone looking out their windows or smoking on their porches can see my radiantly sour head bobbing along above the fence line. Anyone that walks along the hypnotic streets during my hours will hear me whispering poetry in the mush-mouthed voices of bees.

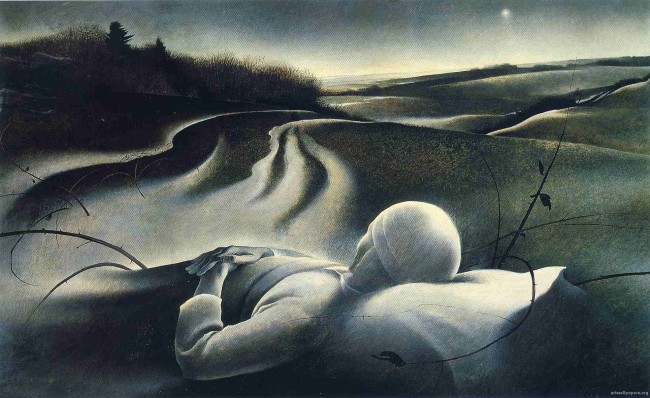

If you listen, I will tell you of beds of roses vomiting in the pale psalm of morning. I will tell you of my daughter, who lives in the patterns of the carpet in the house of a retired philosopher in Brussels. I will tell you about sex, which for me is a solitary act, the melting of matter into other matter, the mutual decay of various ragpicked pieces of flesh and refuse, their slow tantalizingly putrescent cohesion into a one. I will tell you of meadows that hide satanic poetry in their skin, and exude it from their pores on nights with the coldness of bruises.

If you take my hand, my cold hand, my dead and moving hand, I will tell you how to write such poetry yourself.

* * *

It comes across the hall with the sound of little feet pattering, sounding like a vulnerable and frightened child. It is not a child though, but a creature called the Patterfoot. The Patterfoot is a dress-suit-black, umbrella shaped being that hovers in the air through a triad of tiny wings set behind its ‘head’ that vibrate with the speed of a hummingbird’s. (From a distance these wings are designed to merely sound like the comforting hum of a radiator.) It trails two hanging appendages from its body that swing down to the ground, and have attached to their ends small enamel hooves. These hooves are not used for mobility, but are instead manipulated by the appendages, like marionettes from a wire, to clomp along the floor in a manner similar to an excitable, if uncertain, human child.

When a concerned adult steps out into the hall, the Patterfoot propels itself towards them with uncanny speed, like a video that has been sped up, and ejects a noxious gas from a hole in the faceless hood that is its body. This gas at first chokes the air from the lungs like a fist squeezing dry a wet rag, and then slowly, over the period of an hour, deliquesces the body so that what was once a concerned adult named Steve (known to his intimates as Stevie) becomes a stinking puddle of melted matter.

The Patterfoot, being a concerned citizen, looks over this biological hazard and, unsheathing its lures – the hooves – reveals them to be mouths, which it hoovers up the unfortunate waste with.

* * *

The warmness rippled as I huddled against the father-bones. The father-bones were old and feeble but they still held me, still protected me from the dryness and death heat outside. I sent out all my tongues and shadows in greeting to the father-bones after my sleeping time.

It was my duty to protect the father-bones from visitors, the uglyodd and noisy things with their strange waving limbs and sounding holes and clumps of foul-smelling cloth on top. The little things wanted to destroy the father-bones, to erect new child-bones over them and fill them with more things. I had dealt with these thing-beings before. They always brought in their tubes of destructive fire that shot out rays that killed my tongues and shadows and they sometimes stole parts of the father-bones and took them back to their hell with them, their hell of deathlight.

The father-bones had stood here for many sleeping-times, and it was evil to disturb them in their peace. The father-bones held many spirits, held time like water in a carafe, and to evict those spirits or to dry that water was evil. The last time the thing-beings came they brought their tubes of fire and their hot scorching bodies clumped with cloth and began to take things from the father-bones. The father-bones’ tattoo of a stone moon, they wrenched down with their small idiot violence. It was a beautiful tattoo, cracked in places yes, but such lovely cracks, and such a wise old moon. You could tell it held many learned shadows in itself, was plentiful with the wisdom of tongues. It was a gentle coldness that emanated from it, and the thing-beings were going to take it with them.

Though I was afraid, I peered out from my corner and watched them, waiting for the right moment. One of them pulled out a long, hard looking object with a bluntness at the tip and began beating the father-bones with it! At the same time, another thing-being reached out with a hook to pull down one of the father-bones’ beautiful gold earrings. It hung on a silver chain from high up and the stupid thing-being began to tug it down. I had enough. I could hear the spirits screeching in fright in the thick marrow of the father-bones.

I jumped down, although I was still a small girl, and smothered the first thing-being. I put out its heat while it struggled and burned against me, singeing my shadows. I poured cold jelly onto its stench, I breathed water over it, I held it in its burning and smoking till it was still. My body ached with pain. I looked around and saw that the other thing-beings had fled. They were foolish and full of cowardice and greed.

They have not come back since then, but I hear them outside, outside the walls of the father-bones, scurrying and whining and scratching around. I heal for their return, and I wait for them so I can protect the father-bones. I will be ready next time.