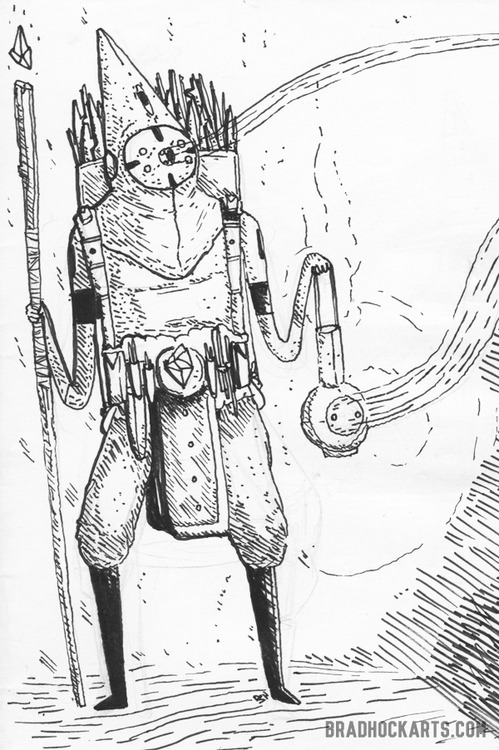

Here is a piece of short fiction I wrote on a whim for a friend, whose art work depicting a fisherman laying rod into a “ghost-hole” inspired me to throw out a frivolous little piece that I had some good fun with (I am now unable to find the exact sketch, unfortunately). It’s a semi pastiche of Southern writers like Cormac McCarthy and William Gay, although I tried to make the twang of the voice a little more understated than I’ve perhaps been guilty of perpetrating in my youth. As I said, it is a frivolity, but hopefully a worthwhile one.

****

I heard the weeping when I was out on my dad’s property. It was way out past the bridge over the dried up gully, where it plateaus and you can see the whole valley; where, if you have a telescope, you can spy on Boont’s Lake ten miles off. See the elk drinking from it, and hawks snatching up fish flying too close to the sun. The weeping hole was in a crevice just below where the tableland drops out.

It was late afternoon. The only sounds were the wind, the crunch of my boots against sandstone and rock, and the occasional lizard, green as lichen, scuttling from crevice to cave as fast as thought. I was enjoying the silence, and the wind behind it. The wind made the silence, gave it the opening to appear; not the other way around. The wind got rid of thought, destroyed the mind and replaced it with itself. Out in that part, the wind is a taxidermist and it’s out to stuff you and your shirtsleeves and brain as thick as rag and cotton. Then the silence mounts you on the wall, and you’re not a person anymore. Just a thing without thoughts.

That’s why a lot of the family don’t go out there at night. But I had things I didn’t want to think about, and this place helped.

While looking at the view afforded me on the plateau, I heard a woman sobbing. I was just rubbing my sore back and I jumped straight up at the sound. Sobbing. All the way out here, and here was basically Outer Nowhere. It takes half an hour on a dirt road to get to my dad’s place and the place out there was five miles into its belly. Nowhere. And here was a woman sobbing and weeping, clear as a woman sobbing and weeping in a police show.

Hey, you alright? I shouted. You okay?

I didn’t get any answer except an echo. The weeping continued. And then I noticed that the woman’s sobbing had no echo to it at all. Her voice landed flat. And everything out on that tableland had an echo, particularly near where the plateau drops off. You threw a pebble out there, it sounded like a .22.

Since she kept on crying, and I couldn’t help but think about things as a result, I set off across the plateau towards the end it was coming from. The sky was getting a little ashy, but this was due more to storm clouds in the east than it getting late. At three o’clock, I still had an hour to get back to my truck near the bridge and drive home for dinner. I watched it slowly moving above me, warily. It was like melted silver stewing about in a great pot.

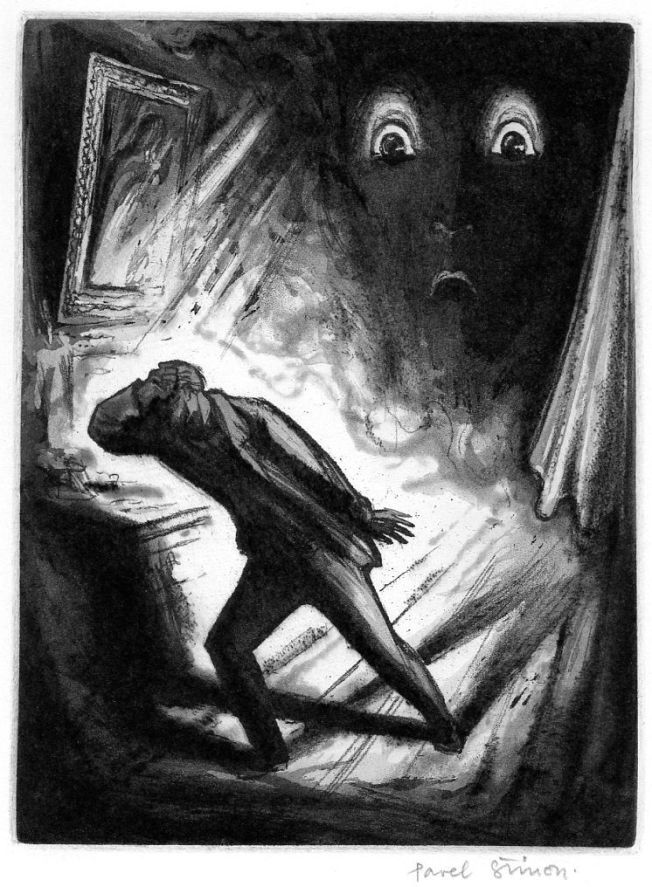

As I strode across the hard red rock the tone of the sobbing seemed to change. It would get fainter, or closer, sometimes deeper. It rang in me like someone pulling a bell in my spine, or scratched in my ear like a dog at a door. Other times it sank away as if somebody had pulled a cloth over the voice, but always it rose up again. By the time I was halfway across the plateau I realized the sobbing wasn’t a woman’s, but a young boy’s.

I walked slower. I was not convinced that it had been a boy all along. It was improbable, and the thing had been unsettling from the outset. It was tough to move along. My feet wanted to turn the other direction and take off. I felt tingling all over them, and tugging too, like they were animals trying to escape from me.

And of course, there was the fact that I could not see this person on perfectly flat terrain, and the table dropped off at the end to a valley perhaps fifty feet below. There were little inlets and protrusions in the rock so you could get down some ways, but you had to be careful and keep balance.

All the time I was walking over to the weeping, no more than two minutes, I did not consider who the voice might be. I did not consider why someone might be out there. I didn’t want to. But I think I knew it was not right, and could not possibly be.

Nearing the edge of the table, I realized that the voice had, very slow and in stages, changed into a drunken old man. His voice was battered unrecognizable by drink. He started with a prolonged and frightful gasping for air, exploded into inarticulate fury, and then returned to gasping once more.

Listening to this in what may as well have been Outer Nowhere was something of an ordeal. I had been crisp and dry and calm, and then two minutes later I was sodden, stinking, hot, and terrified. I pictured this horrible and ruined man crouching against the rock face of the plateau and I wanted nothing to do with him.

And the voice changed again. Quick as a card pulled out of a deck, a young woman was speaking. She was speaking not in general like before, but speaking to me.

I would like some water, she said. Do you have water?

I had almost a quarter of a gallon. I did not answer. The wind was drying out my eyes and I closed them for a moment. Then I resumed walking.

I am very thirsty, could I have water?

I had reached the end of the table. The valley and the voice were below me. I leaned over but could see only valley. And then, almost shattering my heart with its suddenness, the voice said

I wish you would come down here. I really do wish you would.

An old woman said this. I still saw no one, but I received a clear picture of her somehow. Overcooked mutton skin, a thick awful tongue sticking out like a reeking foot, eyes like pissed-in porridge.

I pulled out the long handled hunting knife I kept with me to ward off wild cats. I had a feeling of finality. I knew I had to see this through. The thoughts that had been pressed down by the wind were rising.

The old woman was singing now.

Baby let me play with your yo-yo

I’ll let you play with mine

Hey babe

I’ll let you play with mine

Her leering, cracked voice came from the other side of a rock outcropping. I edged around it, playing nervously with the knife.

When I got to the other side I realized it was coming from a hole in the ground. I stood in front of the hole. Nothing came out of it. The sky above sprouted more gray hairs, glowered and furrowed in

disapproval. This is a desolate land, I kept telling myself for no reason. This is a desolate land.

I crept closer to the hole, getting on my knees. The hole was silent. I reached the edge and stood over it, looking down. There was not a thing to see. I had left my flashlight in the car.

I felt a drop of rain on my neck.

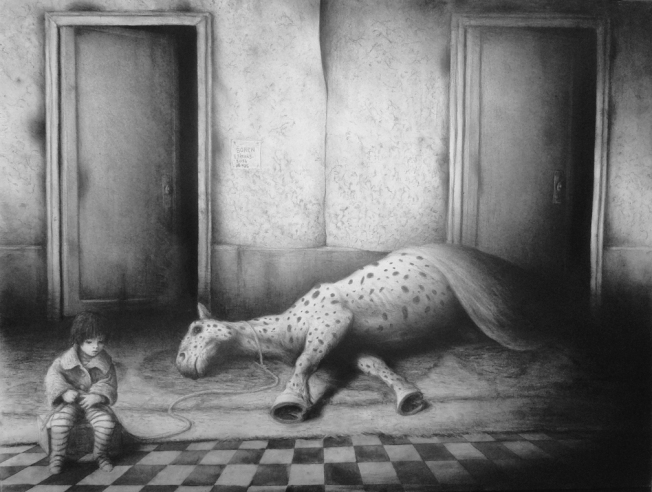

I was considering filling the hole with rocks when my brother spoke to me.

Eldon, you need to get me out of here, he said.

Get you out of there? I asked.

I been trapped in here for months. It’s cramped. I don’t like the company.

I don’t understand, I said. And I didn’t. I really didn’t.

Where you been anyway? Ma’s been looking for you.

Patrick. I don’t know what to say.

How about, how the hell have you been? It’s been months, man. I’m almost done with that wood carving that always annoyed you. The one of the big catfish I caught, that uncle Bibby dropped when we tried to weigh it?

Patrick, that was the ugliest thing I’d ever seen.

Well, hell, it’s pretty good now. You oughta see it. If you get me out of here I’ll show it to you. You never did like any of the stuff I did. Never any of that arsty stuff.

I was just jealous, Pat.

Anyway, get me out of here, yeah? Reach down and give me a hand.

Pat…

Come on, reach and give me a hand.

Patrick, I killed you. Two months ago, I said.

And then there was just silence. The hole didn’t speak.

I started to walk away, dazed, when

What was our mother’s maiden name? Patrick asked. His voice was colder now.

Ma’s name?

Our mother’s maiden name.

Why?

Our mother’s maiden name. Say it.

Tollway, I said. Etta Tollway.

Right on saying this, a head peeked up out of the hole. The head was bashed in on the left side, crumpled up like a gristly red ball of tinfoil. One of the eyes was crushed under the wound, the other gazed out with the curiously blind look of a catfish. On his left ear was our mother’s famous earring, the peridot gem from her grandmother.

The head arched up to the sky like it was going to drink rain and I could see it was wriggling itself out of the hole. I dashed over and ran the knife into its catfish eye as hard as I could, then yanked it out with all of the resentment I’d ever had for him. He fell back into the hole.

The next day I went into Patrick’s old trailer and found the cloth hanging over the carving. I pulled the cloth off and almost lost my balance. When I had last seen it, the trout was not as ugly as I’d lied, but its proportions were bad and it had the weirdly human lips of some pinup girls he kept on the walls. But now it was like something you’d find in a museum. A natural history museum. The Catfish of Northern Montana. It made me hate him all over again.

I stuck it in my coat pocket and took off to Outer Nowhere. I got to the weeping hole, the ghost hole, and stood in front of it. I’m not sure why I was doing it, but it felt like a way of getting the last word in.

It was funny. I’d killed him with the steel flashlight he’d lent me, apparently killed him again with a knife, and I felt like I still hadn’t had the last say.

I held the flashlight and the carving in my hands. I dropped them into the hole.

There was a commotion of voices, and the flashlight must have gotten stuck on the way down, for its light was shining steady down the hole.

There were a bunch of people down there. They all looked up at me with catfish eyes and they had long bony horns coming out of their foreheads. I saw Etta among them, staring glassily at me. Then there was a great whooshing sound and they all came flying up.

Needless to say, I ran back to the truck and did not look back even once.

– Matt Sampaio-Hackney, 2015.