Weird and horror fiction is a tradition that rings with the silence of the unheard. It is a tradition minor to the field of literature itself, and strewn with still more minor writers who have languished, unread, for years. In the long, long scroll of its Great Generic Text there are many neglected passages by authors who produced numerous works, or who just dabbled in the form, or who remained forever anonymous and wrote most of their output in sad and peeling hotel rooms, engulfed in a chalky and tawdry penumbra of cigarette smoke, their organic bodies in a footrace with their words to see which would cease first. (Or, in the case of some pulp writers, to see which could become more cumbersome and preposterous).

For this reason, I’d like to spend a little time recommending and discussing lesser known work from this field, which I have an unhealthy and not entirely explicable fascination with. This will be the start of a series, and the first entry in it features:

Edward Lucas White, “The Snout.” 1927.

Atmosphere is nebulous, hard to create and hard to define. It can’t be restricted to the mere vomiting of adjectival projectiles and constant weather updates. In the right place, a sentence as bare and simple as, “Outside, the streetlights began to turn on,” can exude atmosphere like a hothouse plant emits scent. In the wrong place, a line describing gutters as “yawning their wet gas of rain and garbage” can come off as window-dressing, like a useless and fancy curlicue obscuring an otherwise decent font. It is ultimately not just word-choice but placement, emotion, theme. Creating atmosphere by itself is going about things backwards; atmosphere is the by-product of everything in a story but itself. It is best when accidental, when it arises out of its environment like a weed in concrete. It just happens, but so often it seems to have a life of its own within a text, to loiter reptilianly in an abandoned lot – the only thing we remember about a novel – and to walk about on its own warm legs like a shadow that has left its owner.

Shadow. There is a good way of putting it. Atmosphere is a shadow cast by the body of the text, but without that body it is nothing but air and wishful thinking. You can write a shadow in without a body, but it will be thin as gruel and about as nourishing. (As case in point I would submit Georges Rodenbach’s Bruges la Morte.)

One writer of early horror and fantastic fiction, Edward Lucas White, has to be one of the best at casting the shadow of atmosphere over his reader. In the justifiably famous “The House of the Nightmare,” published in Smith’s Magazine in 1906, atmosphere is dredged up like something evil from a lake in a marvelous economy of words. Without even resorting to more than one or two similes in the entire story, White brings to the tale a grotesqerie and violence, a shimmering hallucinatory quality not often seen in what is structurally a typical Edwardian ghost story.

One of the most desired for effects in horror fiction is that of the dream. A story must have some savor of the dream in it, that bitter taste of the unconscious when it (or they) speaks through you in its wet, dull voice, manipulates and uses the arbitrary assemblage called “you” like a doll. It is also possibly the most difficult effect to achieve, and the most tiresome and unengaging when it fails. In that story, and in others, White manages this effect with a masterful touch. This could be due in certain part to his literally drawing his fiction from his own vivid dreams, but a worse writer could not have replicated the feeling, the moment when (to borrow an image from the artist Suehiro Maruo) the unconscious pulls back the skin of your face and licks your eyeball.

Of his stories, the amazing “Lukundoo,” “The House of the Nightmare,” and “Amina” are probably the most well known, the latter due mostly to an inclusion in a Derleth anthology for Arkham House during its heydey. But I would like to bring to light a different and later story, one with the evocative title of “The Snout.”

“The Snout” begins as an Edwardian crime caper, with savvy crooks planning a heist of the manor of an eccentric old aristocrat, the wonderfully named Hengist Eversleigh, the son of Vortigern (!) Eversleigh. Hengist is an art collector and an artist, and has been accumulating fine horses, carriages, vases, and jewelry for decades. He owns the “biggest stack of loot in North America” and never leaves the confining walls of his manor. In addition, it is said by his hired guards and servants that he locks himself in the manor every night and lets no one in (or himself out) until the dawn. It is speculated that he spends these nights fiddling like Tartini’s Satan or painting.

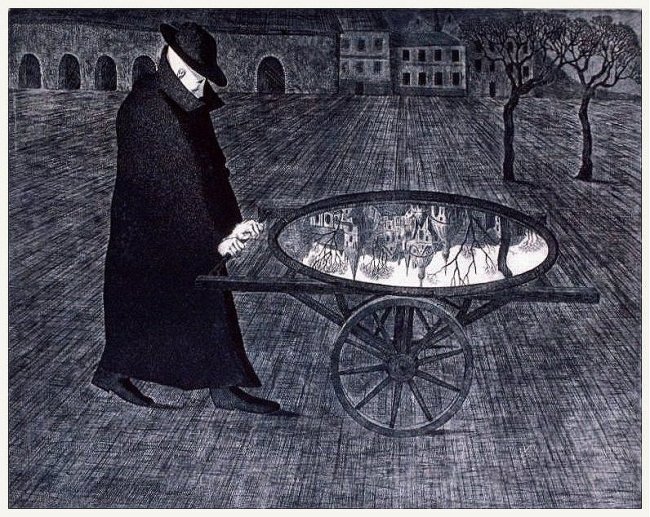

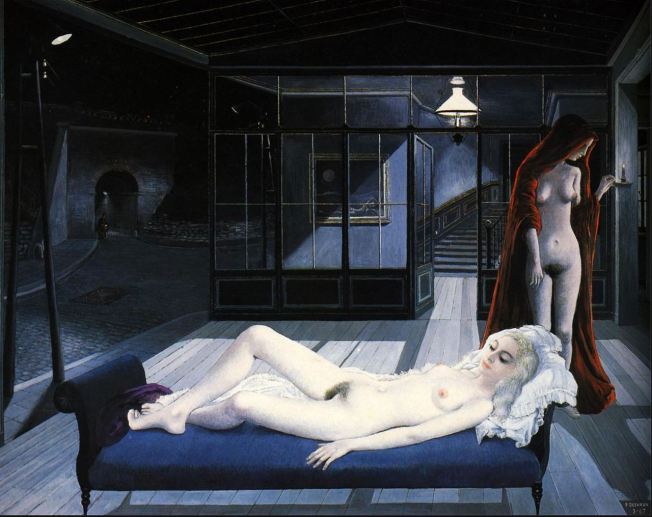

The story proceeds up the winding and lonesome country roads leading to the property, and over the stone walls barring entrance, and through the gates and courtyards of the Eversleigh estate. They are lit with the light, and obscured with the dark, of a Paul Delvaux painting – or so I like to imagine.

As usual for White, without installing any poetic fixtures within the manor of his text he manages to make the reader feel the cool grass of the Eversleigh estate, to smell the rank warmth of the night. His style is that of evocation, to suggest just enough that the reader fills in the rest from the dark matter of their own subjectivity. Thus, I see Paul Delvaux paintings of desolate houses and avenues.

As usual for White, without installing any poetic fixtures within the manor of his text he manages to make the reader feel the cool grass of the Eversleigh estate, to smell the rank warmth of the night. His style is that of evocation, to suggest just enough that the reader fills in the rest from the dark matter of their own subjectivity. Thus, I see Paul Delvaux paintings of desolate houses and avenues.

The story proceeds inside Hengist’s home, through lengthy and unlit galleries and apartments, down and up and across innumerable spinal staircases, etc. Eventually, the crooks find Hengist’s personal gallery of his own work, and it is perhaps the high point of the story.

Close to me when the lights blazed out was a sea-picture, blurred grayish foggy weather and a heavy ground-swell; a strange other-world open boat with a fish heaped in the bottom of it and standing among them four human figures in shining boots like rubber boots and wet, shiny, loose coats like oilskins, only the boots and skins were red as claret, and the four figures had hyena’s heads. One was steering and the others were hauling at a net. Caught in the net was a sort of merman, but different from the pictures of mermaids. His shape was all human except the head and hands and feet; every bit of him was covered in fish-scales all rainbowy. He had flat broad fins in place of hands and feet and his head was that of a fat hog. He was thrashing about in the net in an agony of impotent effort. Queer as the picture was it had a compelling impression of reality, as if the scene were actually happening before our eyes.

Hengist Eversleigh’s paintings seem to predate some of the works of Max Ernst, especially the mythologically derived animal-heads of Une Semaine de Bonte. The hog-headed man is reminiscent of the frightful episode from “The House of the Nightmare” where a giant sow attempts to clamber up a bed. “Mr. Hengist Eversleigh is a lunatic, that’s certain,” one of the characters says; “but he unquestionably knows how to paint.” The home invaders of course eventually meet Mr. Eversleigh, after a long trip through the enormous manor and its many and curiously child-sized apartments and furnishings. I will say no more of it, but it is one of the finer pieces I read in S.T. Joshi’s The Stuff of Dreams: The Weird Stories of Edward Lucas White, published by Miskatonic Books. I would recommend purchasing the volume, but it is pricey and of somewhat crappy quality in terms of printed material. Instead, I’ll point to this link, where you can read a number of White’s stories including a few not included in The Stuff of Dreams: Darkside Fiction.