I’ve always enjoyed fiction about artists and musicians, much more so than I have enjoyed fiction about (or featuring) writers. The endless procession of texts taking The Writer as their subject strides arrogantly towards infinitude, and particularly in genre horror, the protagonist is often a writer in rural retreat or barnacled against the rotting mast of some city tenement while they torture themselves for their masterpiece. This is such a grossly easy device for the actual writer to avoid having to invent the realistic voice of a non-writer, that I would rather have the inanities you see in early pulp fiction:

‘Its liquescent mass is putrescently loathsome!’ cried the illiterate mill-worker.

And other such tripe. I find this preferable to Karl Edward Wagner’s succession of writers and fiction enthusiasts who are all coincidentally really into Black Mask magazine and Oliver Onions. My god, that creature over there looks remarkably similar to something I once saw in a Lee Brown Coye drawing, and now it’s clawing my balls out, oh god oh god my balls.

Fiction about painters and saxophonists and pianists is less inward, in the general run. Such a choice of subject requires its own problematic luggage to be hauled up the stair, but seems to me much less prone to preciousness and veiled self-mythology. From James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” to Violet Paget’s “A Wicked Voice” to Ann Bridge’s “The Song in the House” to H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Music of Erich Zann” to Sax Rohmer’s “Tcheriapin” to Kalamu ya Salaam’s “Buddy Bolden” to Robert Chamber’s “The Mask” to Edgar Pangborn’s “The Music Master of Babylon” to Henry Dumas’ “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” to Walter van Tilburg Clark’s “The Portable Phonograph,” the list of tales I’ve loved about music and musicians, art and artists, is very long indeed. Perhaps it gives a glimpse into a medium which remains far more mysterious and occulted to me than the one I sadly labor at; perhaps I just enjoy the fabulation of Pierre Menards, or the waking into a wedge of historical context, peering over the stile at a fertile creative period in history.

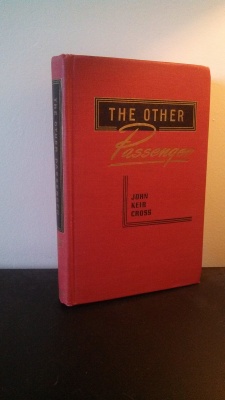

Or perhaps that’s just a bunch of shit, and the fingers which transmit this message are burning with stupidity beamed down from the turd floating in the punch bowl of my skull. My cretinous, cretinous skull. Notwithstanding, for these reasons and others, John Keir Cross’ 1946 fiction collection of SF/fantasy/horror, The Other Passenger, endears itself to me. “Valdemosa” concerns Frederic Chopin’s relationship with George Sand in Majorca. “Clair de Lune” is set in a British artist colony around the time of the first world war. “Couleur de Rose” deals with Tin Pan alley singers and songwriters.

“Valdemosa” is a concise and clear portrait of Chopin’s misery and illness, and the strangeness of one’s beloved, who in the night, appears sometimes to have wandered into one’s bed like an animal. The tale ends with Sand looking down at Chopin, seeing him as an unknowable, frail boy, “stricken…in [her] arms.” “Clair de Lune” is another suitable candidate for this series, a tale of a woman appearing on the lawn and beings called Dark Ones, invisible and sinister, flowing all around her. “Couleur de Rose” is not as strong as either, but its portrait of the song-hocking lifestyle from that era is worthwhile. Yet the highpoint of the collection, aside from the excellent and moderately-anthologized “The Glass Eye,” is another tale of art and artists: “Miss Thing and the Surrealist.”

Surrealism is at its height at this point – a fully bloomed carnation with a small child’s bloody eye lodged in its petals – and Cross concerns himself with a group of British practitioners and aspirants to the movement. Their world is one of junk-shops and dream poetry, disgusting similes and dead fireplaces filled with beer bottles, and ultimately, a horribly angled continuum between art and reality.

Like a number of Cross tales, “Miss Thing” is filled with strong, idiosyncratic women, and the surrealists in this piece are evenly split by gender – an egalitarian state, which, at least in the histories of surrealism, did not exist. Even now, numerous wonderful artists are relegated to the status of lovers and hangers-on of apparently more important men – Dorothea Tanning to Max Ernst, Unica Zurn to Hans Bellmer. Not so in this tale, where the one artist agreed to be touched with actual genius is a woman named Chloe Whitehead. (As Leonora Carrington said when questioned about the association of surrealism with masculinity: ‘Bullshit.’)

But “Miss Thing” does not take Chloe Whitehead as its focus, nor Tania, nor Jo Haycock, nor Howard Darby – but a reclusive surrealist named Kolensky, and his artistic creation, Miss Thing. It seems to me in this way that Cross (or at least his text) takes a more sinister look at surrealism and its pretense and desire to transcend the given, and its failure as a liberatory practice. More specifically, we have a harsh representation of the surrealist techniques of bodily transformation and mutilation. “Miss Thing” is, in its way, a piece within the sub-genre of ‘body horror.’

Cross’ narrators are often perceptive outsiders who make cutting observations about the social groups around them, and this tale is no exception. The artists are depicted as largely more concerned with their lifestyles as artists, and the appearance of being artists, than the actual production of art itself.

We were concerned with being artists. We looked like artists. We behaved in a manner. Our mode was intended as some sort of gesture – a rude one – five extended fingers at the nose aimed at – what? (All that we secretly were, perhaps, and were afraid or ashamed of.)

These particular British surrealists are afraid of being bourgeois, and in order to stave off this fear ritually frighten or unsettle the bourgie’s so that they may distinguish themselves. Their social methods of declaiming themselves different and radical and surrealist are very amusing. “Miss Thing” is filled with wonderful little details, fictional crown-moldings and cornices sitting prettily in the edifice of text. The writerly surface called style, as Sam Delany would say, shimmers with Cross.

Some of us were walking along the King’s Road with some people – some cousins of Tania’s. We passed a tall house with a woman shaking blankets out of one of the upper windows. Some feathers were fluttering to the ground and the large loose white thing waving seemed like a bleached tongue out of a toothless oblong mouth.

“Oh look,” cried Tania, “that house is being sick…”

Or in another instance, my favorite:

Howard took us all to a crowded and noisy little restaurant that we knew of, where there was music and a permanent buzz of conversation. He had just been reading an anecdote about Baudelaire. He waited for a moment when the music stopped suddenly and the clatter dropped for an instant, then said in a loud tone as if continuing a conversation he had been shouting through the din –

“…but have you ever tasted little children’s brains?”

Yet the amusing hijinks of surrealists frightening the bourgies is just more of that immersive shimmer Cross covers his fictions with. The real concern is with the enigmatic Kolensky, his house, and his marriage to an upper-class, fundamentalist Christian named Vera. Not just a bourgie, but a member of the ruling class! And she is so disconcertingly blase about Kolensky and his transgressive art – as if she weren’t suitably impressed and offended by it. She is the “incarnation of all we gestured against,” but their gestures do not work. For their honor as surrealists, this woman “from Putney or Wimbledon” must be defeated. So, we have Vera in one corner, and Miss Thing in the other.

Who or what is Miss Thing? You meet her when you go to Kolensky’s door at his rooftop apartment; you reach out to her waxen hand, the knocker, to announce your presence. You are allowed in and acquainted with her further when you see her legs holding up the mantle, one breast as a flowerpot, the other breast in the wall, the feet at the bottom of a curved chair – and the other hand the flush chain on the toilet. Miss Thing is an involved and permanent art installation, and Kolensky’s fellow surrealists think she/it is the highest example of surrealism, not only because of the sculptural accomplishment but Miss Thing’s fact as an incarnation of surrealist living.

And who is this Kolensky, then? An odd, nothing-man. Forty or forty-five. A heavy sleeper, inarticulate, with a “leonine mop” of hair. The sort of ghost George Sand thought she saw when she looked down at Chopin sleeping in her bed. A flickering image. A torso without guts, a mouth minus teeth. A novel without a verb. Cross says, in his easy manner:

He wore a beard – it was one of his disguises. (I did myself in those days, for there is always a time – at least one time – when you must from yourself disguise yourself. Later on you realise that when you meet your own ghost sitting quietly and accusingly on your doorstep when you go home at night, he must look like you yourself, or he has, poor soul, no meaning.)

For the surrealist circle in this tale, Kolensky’s status as penultimate surrealist is rooted in his house. His paintings they say are accomplished, but no one ever remembers them. It is that incarnated surrealist, Miss Thing. She makes Kolensky, even more than he made her. And Kolensky is just a disguise with nothing under it.

To the disappointment of the surrealists, prim society girl Vera does not mind Miss Thing at all, but changes and waters the flowers in her breast, polishes her legs, and so on, without a single hint of discomfiture. She is unfazed, or she loves Kolensky too much to show it.

(Spoilers to follow).

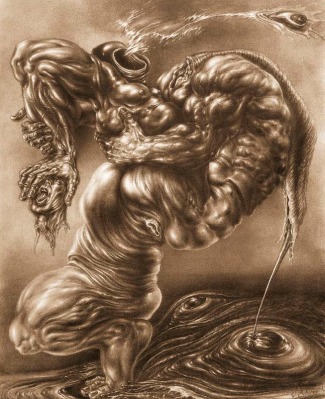

One of the more unusual quirks about Cross’ fiction is that he alternates between drawing sympathetic, fleshed-out portraits of odd, marginal women (esp. in “Glass Eye”), and on the other hand, partaking of the classic misogynist trope of fictionally destroying (and lovingly lingering on the destruction of) women’s bodies. “Miss Thing and the Surrealist” is not quite situated in either tendency, but it does bring to fictional life a frightening literalization of the work of many male Surrealist artists, who so often dismembered, disfigured, and tortured the bodies of women in their painting and sculpture.

Dorothea Tanning, Hotel de Pavot. Trans and dis-figurations of the human body weren’t solely done by male surrealists to women’s bodies, but were also part of a larger tendency in modernist art to sculpt and distort the body and eradicate boundaries of the self.

The unflappable Vera appears at first to win the battle without even realizing one was taking place. She continues to water the breast, go to church each morning, dote over Kolensky and unconsciously irritate all his friends. But one day Vera goes through Kolensky’s old papers in his desk and finds a marriage certificate, certifying his marriage to another woman. And Kolensky had never mentioned a word of this or of any divorce; he might have even married her, Vera, in bigamy! This was unconscionable. In her dismay, she ends up looking more closely at Miss Thing’s parts and realizes that they are “not wax at all – embalmed! embalmed!” Kolensky’s art installation is made from the corpse of his first wife, whom he presumably murdered. Miss Thing is Mrs. Kolensky 1.

(This twist is sort of like the old Pan Horror story, “The Ohio Love Sculpture.”)

Vera, however, is more horrified about the bigamy part. She goes to the law but only because of the marriage’s false pretenses. The murder, the embalming, do not really bother her so much as the fact that bigamy is against her creed. She is revealed to be a monster in her own, lesser way, under the shadow of Kolensky’s monstrosity.

Kolensky is hanged, an event the surrealist circle find grimly appropriate to their “King.” And they all disperse. Chloe Whitehead ends in a mental institution. Tania becomes an actress, Jo married. Fin.

What we have here seems to me the disillusionment of surrealism as a method for extricating oneself, freeing oneself, from the ideologies and taboos and expectations around one. It is the failure of a liberatory practice. The burrowing into the unconscious, into the world of dream was to herald a freedom or liberation from the perversities and ideologies of capitalist society. As Andre Breton said in a lecture in 1934:

Today, more than ever before, the liberation of the mind, demands as primary condition, in the opinion of the Surrealists, the express aim of Surrealism, the liberation of man, which implies that we must struggle with our fetters with all the energy of despair; that today more than ever before the surrealists entirely rely for the bringing about of the liberation of man upon the proletarian Revolution.

But in Cross’ vision (the vision of a man who may not be sympathetic to such a goal in the first place), his penultimate surrealist Kolensky burrowed into the unconscious to escape from the world above, only to drag up a horrific revenant, a malformed mirror-image of a thing from that world above: the misogynist conception that men own women, whose bodies are their property by right. Mrs. Kolensky was just another canvas.

Yet it is not just an instance of the misogynist under and over-tones of male surrealist work being incarnated in reality, but is also part of a larger tendency in surrealism – the desire to escape from the physical and enter the dream-world. And in a grim sense, one could be tempted to say this is what happened to Mrs. Kolensky. But she did not enter the dream world; Kolensky did.

This tale seems to coincide with or confirm the work of Paul Virilio, who in Art and Fear draws a connection between the work of modernist artists who warp and disfigure the human body with the insane sciences of war and the death camp. As Davin Heckman put it, “He tells a history of art that dreams of a world without humanity, and a history of science that is already bringing this dream to life.”

With “Miss Thing and the Surrealist” we have a representation of surrealism as a somewhat egalitarian art and practice, but one still not fully severed from the awful ideologies of the world it was supposed to be fighting against. Kolensky’s masterpiece is like the work of Hans Bellmer or Dali literalized, with any potential liberation (from the body in general, from more specific conceptions of feminine beauty, from the Pedestal) negated and turned into death.

If it is not clear already, Keir Cross is a marvelous writer on the level of prose and the generation of meaning and aphorisms. I’ll end the review with a quote from this tale, a darker twist on an old cliche derived from Carl Sandburg:

My friend, there are layers and layers. Life, said Howard once, is like an onion. You peel the layers and there is no core. It only makes you weep.