“Tales of the Grotesque” in a new paperback edition by the UK’s Shadow Publishing.

I first heard of the British writer Leslie Allin Lewis (1899-1961) through John Pelan’s marvelous door-stopper Century’s Best anthologies. The inclusion Pelan decided on (operating on a one story per author basis) was “The Tower of Moab,” an arresting and visionary blear of oddity. It was one of several pieces in the collection that seemed to reach beyond its historical context and not merely gesture towards the future, but grab that future by the windpipe and throttle it. It was like Ligotti with the nihilism replaced with mysticism, and shorn of the tendency toward over-writing, yet to summarize it in such a neat way is both a disservice to Ligotti and to Lewis.

Like the work of another Edwardian weird writer, Edward Lucas White, there are no standards or fixtures of horror iconography in this collection, Tales of the Grotesque, recently reissued in affordable paperback by Shadow Publishing. There is not a single straight forward haunting or conventional monster. Instead, you find: the director of music for a local church stumbles on chords that open a rift between this world and another while in somnambulistic trances (“The Chords of Chaos”); a quake opens a hole in the earth, out of which come absinthe-colored entities that linger in the air and terrorize RAF pilots (“Haunted Air”); a traveling salesman goes on a drunk bender and sees visions of demons and angels hovering around a derelict tower built by a religious cult in the late 19th century (“The Tower of Moab”); a man believes his body has been taken over by a past incarnation, one that was burnt at the stake for witchcraft and manifests itself as a perverted feathered creature (“The Hybrid”); a girl falls into a different dimension while on a boating expedition, where she suffers a horrible form of torturous un-death being eaten by unearthly fish in a strange, greenish pool (“Animate in Death”).

Lewis is concerned with the ineffable, with his theosophical bullshit about the astral plane and the web between this world and another, but this concern is intimately bound with earthly grue, with black blood and tobacco-brown bones, and the guts that move inside us – the being that squirms beneath the skin. The mystical is clothed in flesh, and the dangers posed by piercing into the other world are not merely psychological. In “Lost Keep,” such veil-piercing is used to awful ends, as a power-hungry man transports his enemies to a mysterious castle surrounded by a limitless ocean, and leaves them to starve to death, or murder one another. At the end of the piece, the keep in question has been more or less turned into a Dakhma, or Tower of Silence, pungent with flesh, bursting with rot.

The Theosophical Society recurs throughout the collection, an entity frequently referred to by various narrators and protagonists, who oftentimes will subscribe to its newsletter or write articles for its publication (much as Lewis himself did in his life). They are a bureaucracy humming in the background of the stories like the faint sibilation of a radio from another room. They are an authority; they posses gravitas; they might explain things – except they don’t.

In the collection’s best story, “Animate in Death,” an amateur psychic investigator comes up against a force he has not exactly been prepared for by his theosophical reading and his experience with the society. In a humorous take on the psychic investigator genre, Lewis says, through the character: ” ‘It’s queer,’ he mused aloud, ‘how the man in the street always regards an occultist as a sort of case-hardened miracle-man. He is expected to go out into the most horror-haunted regions and hobknob with the Powers of Darkness as though they were a bunch of lawyers’ clerks.'” The investigator has a vague concept of what he is dealing with, but nothing more, and at the end fails to save both himself and the victim, effectively dying to save her. This sacrifice is not handled well emotionally in the text, and is executed on an off-note, but that sense of failure of dealing with such supernatural matters is palpable throughout many of these tales.

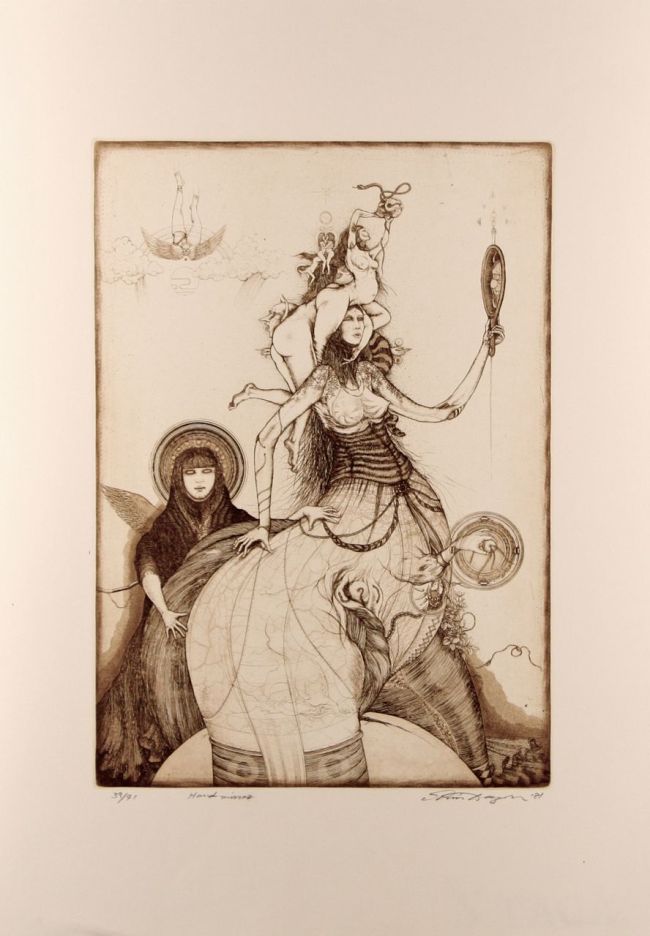

The edition I wish I had, and which costs about five beach-front houses.

Much of horror and weird fiction hinges on the conflicted relationship between terror and humor, the author’s deft handling of the text and modulation of its tone determining that it does not stray too far in the direction of the comic. A clumsy, ardent writer will pile on the elements of the horrible so that the fictional scale topples over on the side of the ridiculous. This can be used for intentional effect sometimes, particularly in such sub-genres as bizarro. However, several of Lewis’ stories reside in an uncomfortable zone in between the horrible and comic, uncomfortable both in the sense that they are successful examples of weird fiction and that they are disconcerting and jarring to the reader, who wonders how much control Lewis had over that tone’s manipulation.

The tale “The Hybrid” is one of these, concerning the aforementioned man being possessed by a wicked past self. His body begins to take on the qualities of a monstrous, half-human fowl, shambling around like a drunkard and hopping up on dressers and tables, perching on any height at hand. This quality seems preposterous, laughable, until the hybrid in question assaults the man’s wife in the yard. The description of the hybrid suddenly running with its odd limp at her marks a sharp twist of the dial between the silly and frightening.

In his introduction, editor Richard Dalby mentions that Lewis was invalided out of the RAF in the 1940s, and began a stage of his life in which he was faced with perennial under-employment. During this period, he destroyed all of his unpublished work “during a fit of manic depression.” Dalby speculates that these destroyed stories, like the “bitter drawings” allegedly made by Bruegel in his later years and which were burned, were too disturbing for publication at the time. It is difficult to imagine Lewis writing a story more disturbing than “The Author’s Tale,” in which the quietly sadistic author in question leaves his wife to be devoured by a band of flesh-eating, pseudo-vampiric ghosts – but there you go. It is a shame they are lost, but at least Tales of the Grotesque survives.