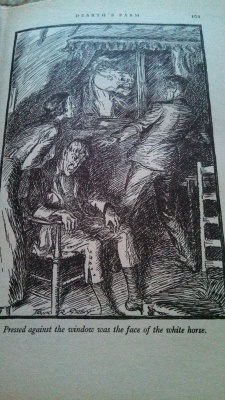

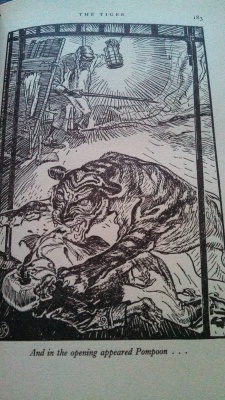

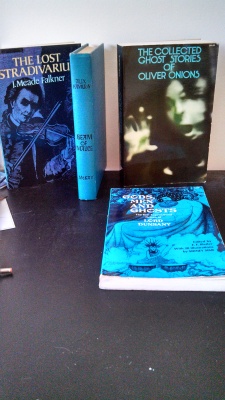

Thought I’d go over a great old anthology, The Mammoth Book of Thrillers, Ghosts and Mysteries, edited by J.M. Parrish and John R. Crossland and published by Odhams Press in 1936. It’s a musty old thing, embossed with a flying bat on the cover and filled with illustrations by a variety of magazine illustrators from the era. It has a sealed section at the end, comprising many of the choicer terror tales, and marked with hyperbolic warnings about reading alone and at night. Each selection comes with its own author portrait, drawn by an unknown artist or series of artists. Some of these are rather bad, such as the oddly sinister one of M.R. James, where he looks like some sort of angry banker who has just found out his workers are unionizing – but others are quite good, such as Aldous Huxley and Guy de Maupassant. (The purveyors of the illustrations themselves are credited on their own page.)

I picked this up for 12 bucks about two or three years ago, so my memory of the contents is not as vivid as it could be, but I write down all the decent stories I read in a notebook so that helps. I’m not going to give this a serious critical dressing-down, as this is more about providing a casual look-through at a relatively easy to find anthology which is still running at an affordable price and is packed with lesser known contributions to the tradition of British strange fiction.

Some of the highlights are Michael Arlen’s “The Ghoul of Golders Green,” a story so enjoyable I didn’t even mind that it had a blazing atrocity of a crap ending. This was my first introduction to Arlen (the former Dikran Kouyoumdjian), an acquaintance I was glad to extend when I later read his excellent and uproarious “The Gentleman from America.” J.D. Beresford contributes an enigmatic puzzle of a tale in “Powers of the Air,” a piece that might give Robert Aickman a run for his money in the unpopular ‘How Many Unexplained Things Can You Have in Your Story’ contest.

Joseph Conrad’s unremittingly tense “The Secret Sharer” is included. A piece by the aforementioned Mopin’ Maupassant, “The Hostelry,” also quite strong and atmospheric; a man keeping watch over an out of season and snowed-in hotel, deep in some European mountains whose specific location I can’t bring myself to give a shit about and remember.

Huxley’s “The Dwarfs” is great, James’ “The Mezzotint” is one of my favorite bits by him (I’ve included the illustration for it below). Jerome K. Jerome’s “The Dancing Partner” is here, and it is a deserved classic, brutal, abrupt, and horrid in every way. Onion’s “Rooum” is solid, Barry Pain’s “The Green Light” is a fun but slighter offering from him.

Robert Louis Stevenson steals a folktale from Hawaiians and comes out with “The Island of Voices,” likely my favorite thing by him. The anonymous “Tale of a Gas-light Ghost” is tremendous, which I was not expecting at all. I had my first dalliance with L.P. Hartley here, in the well-known “A Visitor from Down Under,” which is as humorous as it is unnerving, and condenses everything I love about the British style of doing weird, odd, and strange fiction.

William Hope Hodgson also contributes his woeful tale of fungal foibles in “The Voice in the Night,” which still astounds me that it was written in 1907 and is so thoroughly and wonderfully cruel, disgusting, and funny. This was quite a bit before the housing fungal-fiction bubble in the late 20th century, long before the gob of fungi became a standard device and fetishized accoutrement in the world of weird fiction.

I can remember little of P.C. Wren’s “Presentiments,” but I graded it an ‘A’ in my notebook so it must have been good. It was Freudian, as I recall, about a smothering and jealous mother who hounds her daughter into an early grave and is not even consciously aware of her own smoldering hatred for her offspring.

This anthology is still out there and relatively affordable, and it comes with my entirely worthless and dubious recommendation. Apparently this post has screwed up my blog’s format, somehow, which irritates me to no end but which I don’t feel like doing anything about now.