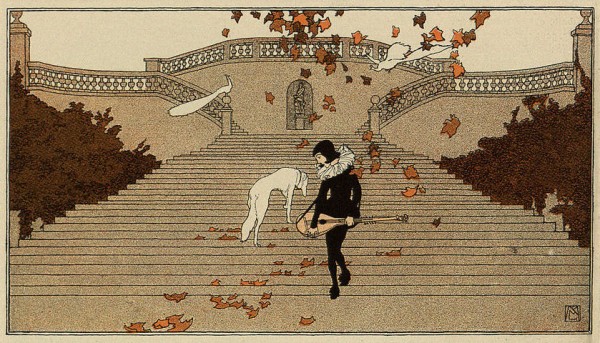

Mila Von Luttich, Untitled, Figure walking up Staircase.

I have been a bad blogger. I am about to embark on reading Wakefield Press’ new Gabrielle Wittkop books, Murder Most Serene and Exemplary Departures, and will write a lengthy piece on them; in the meantime, here is a potpourri of prose from books I have read in the last handful of months. I may or may not muster enough ambition in between to tackle a polemic on the growing commercialization of the Weird, but I will if I can. Other books I will be reading after Wittkop and hopefully writing about will be Anne Hebert’s The Children of the Black Sabbath, Andrew Sinclair’s Gog, Claude Seignolle’s The Accursed, and Djuna Barnes’ Ryder.

From Gabrielle Wittkop’s The Necrophiliac:

I don’t hate my occupation: its cadaverous ivories, its pallid crockery, all the goods of the dead, the furniture that they made, the tables that they painted, the glasses from which they drank when life was still sweet to them. Truly, the occupation of an antiquarian is a situation almost ideal for a necrophiliac.

From Jack Black’s You Can’t Win:

His eyes were small and cunning. They looked as if they had been taken out, fried in oil, and put back.

From W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn:

The capital amassed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through various forms of slave economy is still in circulation, said de Jong, still bearing interest, increasing many times over and continually burgeoning anew. One of the most tried and tested ways of legitimizing this kind of money has always been patronage of the arts, the purchase and exhibiting of paintings and sculptures, a practice which today, said de Jong, was leading to a relentless escalation of prices paid at major auctions….at times it seems to me, said de Jong, as if all works of art were coated with a sugar glaze or indeed made completely of sugar, like the model of the battle of Esztergom created by a confectionist to the Viennese court, which Empress Maria Theresa, so it is said, devoured in one of her recurrent bouts of melancholy.

From Alfred Kubin’s The Other Side:

My pictures, soaked in the pallid, gloomy atmosphere of the Dream Realm, were a veiled expression of my grief. I spent hours immersing myself in the poetry of the dank courtyards, hidden attics, shadowy back rooms, dusty spiral staircases, abandoned, nettle-ridden gardens, the pale colours of the brick and wooden pavements, the black chimneys and a whole host of bizarre fireplaces. They were repeated variations on one melancholy theme, the anguish of desolation and the struggle with an unfathomable fate.

Natalia Smirnova, Grimoire.

From Gerald Kersh’s Fowlers End:

I don’t believe them when they say that wisdom is something gently acquired. It may come gradually over your head, but it hits in a flash and with a shock. Such wisdom as you have strikes like lightning, and you are none the happier for it – if you are wise. I can liken it only to a sudden and agonizing eructation of perceptiveness, upon whose sad wind your years of innocence are belched away, leaving a bitterness which it takes all the years of your maturity to purge you of – if you are lucky.

From Pierre Mabille, The Mirror of the Marvelous:

Lovers are infallible diviners. Renewed by emotion, their eyes wash clean habit’s dust from things and so perceive their total reality.

From Joris Karl Huysman’s La Bas:

He sobs as he walks along. He attempts to thrust aside the phantoms which accost him. Then he looks about him and beholds obscenity in the shapes of the aged trees. It seems that nature perverts itself before him, that his very presence depraves it. For the first time he understands the motionless lubricity of trees. He discovers priapi in the branches.

Here a tree appears to him as a living being, standing on its root-tressed head, its limbs waving in the air and spread wide apart, subdivided and resubdivided into haunches, which again are divided and resubdivided. Here between two limbs another branch is jammed, in a stationary fornication which is reproduced in diminished scale from bough to twig to the top of the tree. There it seems the trunk is a phallus which mounts and disappears into a skirt of leaves or which, on the contrary, issues from a green clout and plunges into the belly of the earth.

Frightful images rise before him. He sees the skin of little boys, the lucid white skin, vellum-like, in the pale, smooth bark of the slender beeches. He recognizes the pachydermatous skin of the beggar boys in the dark and wrinkled envelope of the old oaks. Beside the birfucations of the branches there are yawning holes, puckered orifices in the bark, simulating emunctoria, or the protruding anus of a beast. In the joints of the branches there are other visions, elbows, armpits furred with grey lichens. Even in the trunks there are incisions which spread out into great lips beneath tufts of brown, velvety moss.

Everywhere obscene forms rise from the ground and spring, disordered, into a firmament which satanizes. The clouds swell into breasts, divide into buttocks, bulge as if with fecundity, scattering a train of spawn through space. They accord with the sombre bulging of the foliage, in which now there are only images of giant or dwarf hips, feminine triangles, great V’s, mouths of Sodom, glowing cicatrices, humid vents. This landscape of abomination changes. Gilles now sees on the trunks frightful cancers and horrible wens. He observes exostoses and ulcers, membranous sores, tubercular chancres, atrocious caries. It is an arboreal lazaret, a venereal clinic.

And there, at a detour of the forest aisle, stands a mottled red beech.

Amid the sanguinary falling leaves he feels that he has been spattered by a shower of blood. He goes into a rage. He conceives the delusion that beneath the bark lives a wood nymph, and he would feel with his hands the palpitant flesh of the goddess, he would trucidate the Dryad, violate her in a place unknown to the follies of men.

He is jealous of the woodman who can murder, can massacre, the trees, and he raves…

Yaroslav Gerzhedovich, Dandy in the Underworld.

From Robert Harbison’s Eccentric Spaces:

Like all converts, Huysmans supposes he does the faith a favor by becoming interested in it.

From Arthur Machen’s The Three Impostors:

“You are enlightened, I think; you do not consider all the petty rules and bylaws that a corrupt society has made for its own selfish convenience as the immutable decrees of the Eternal.”

(I forgot to mention: the title of this post is a quote from a poem by Arseny Tarkovsky, the father of film director Ivan Tarkovsky.)