-

Xavier Mellery, La Escalera. 1889. The painter quoted in “Ravissante” as saying he paints “‘silence’ and ‘the soul of things.'”

Just yesterday, I re-read an Aickman story I first encountered in a Ramsey Campbell anthology called Uncanny Banquet. That story is “Ravissante,” first published in 1968 in his collection Sub Rosa. What follows will deal in spoilers, so for those that have not read “Ravissante” and plan to read it at some point, you should probably not read further. It is a story worth reading, particularly to those who have an interest in symbolist and decadent painters from the fin de siècle period. Xavier Mellery, William Degouve de Nunques, and James Ensor are all mentioned, among others. An antique Art-Nouveau house in Brussels features prominently in its setting, for what it’s worth. And besides all that, it is a beautiful and mysterious story, and who doesn’t want to read one of those?

“Ravissante” (French for ‘charming,’ by the way) falls in line with my feeling that most Aickman stories are more enjoyable when you re-read them, but it also differs in another respect. I do not find this story unsettling or frightening in the way his best fiction is. I did not the first time, and did not the second. Nonetheless, it is a fascinating story, and one of his most perverse and unusual (second only perhaps, to “The Swords”).

“Ravissante” is a story within a story, of the “manuscript found in a drainpipe/toaster oven/bottle of laxative/etc.” variety. The typical Aickman introvert cipher narrator strikes up an acquaintance with a painter at a forgettable cocktail party. He is a dry and forgettable man, “faintly disappointing,” but a painter of some power. His wife is even drier and more forgettable, a taciturn matchstick of a woman who says almost nothing at all and whose character never moves beyond the enigmatic. The painter dies, and bequeaths his entire artistic output to the narrator – as well as a hundred pounds, for some reason. The narrator meets with the painter’s wife, who indifferently says she will burn everything he does not take. He takes one painting and a stack of papers that consist of the man’s letters and writings. The narrative proper begins when the narrator reads one of these papers, a tale chronicling the painter’s stay in Belgium, visiting the elderly wife of an unnamed symbolist painter.

This is, of course, the point at which the story splits itself in two, where the main narrative shrugs off the old skin that held it and slouches off somewhere else. The common problem of how to connect these two parts is present here in “Ravissante,” and it is worth noting that Aickman does not even try to resolve it. He simply allows the manuscript to complete itself, and then fucks off without another word.

The painter – who remains anonymous throughout the story on the basis of that rusty old verisimilitude-contraption that in the Victorian and Edwardian periods expressed itself like “Monsieur M____ gave me a snot filled handkerchief at the Hotel rue de _____”- spends much of the narrative within the stately home of Madame A. It is apparent that this house exists on a different plane of reality than we find in the earlier section of the story. Madame A herself is imperious, the house is dimly lit, and reality seems to take on a discomfiting, liquid aspect.

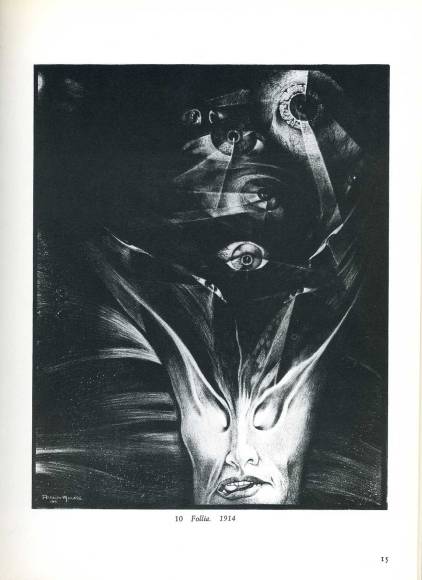

Alberto Martini, Follia. 1914.

The main room of the house is a long living room replete with symbolist sculpture, erotic works by Felicien Rops, smoked-glass Art-Nouveau lamps, and an enormous fireplace sonorously belching with flame. The painter notes, “Almost as soon as I entered, it struck me that the general coloration had something in common with that of my own works” (p.14). This is a theme Aickman goes on to elaborate at (subtle) length.

Madame A regales the painter with lurid, salacious tales of the personal lives of many artists she knew, saying of one, “I wouldn’t have used him as a pocket handkerchief when I had the grippe” (see how this story has burrowed into me, with the re-appearance already of a mucus-soaked handkerchief). She rants and gripes and berates and belittles, and you can smell the stale hovels, stinking feet, furtively spilled seed, soured wine, and odd fetish acts implied in her harangue. The painter is mortified, feeling that she is spoiling the dignity of the artists he adores. But he says nothing, knowing that only command “interested her in the context of human discourse” (p.13).

While she fumigates her own memories of the repulsive, insect-like artists she knew, something very odd happens. A small dog, looking like a black poodle, appears out of a shadowy corner behind a door and pokes around the sitting area by the fire, and then trots away back into the darkness, entirely unnoticed by Madame A. The painter says that it has “very big eyes and very long legs, perhaps more like a spider than a poodle” (p.19). He relates this to Madame, suggesting it “must have got in from the darkness outside,” but she shrugs and replies that animals are always making appearances in the room, including “less commonplace species” (p.20).

The strangest part of the story occurs when Madame A invites the painter into the room of Chrysothème, her currently-abroad, adopted daughter. She makes a number of curious statements about her, saying that she “is the most beautiful girl in Europe” and that, “If you could see her naked, you would understand everything” (p.20). The most important parts of Aickman’s description of the room follow: “In the center of the far wall stood a red brocaded dressing table, looking very much like an altar…the only picture hung over the head of the bed in the corner behind the door” (p.21).

At this point we have entered an inner chamber of the house’s reality. If the main room with its possible doors and artifacts of memory is an in-between zone, the room of Chrysothème is closer to the heart of it, maybe to the “silence” and “soul of things” as Mellery is quoted earlier.

The painter dully exclaims that it is a “beautiful room” and receives the reply from Madame A, “That is because people have died in it…the two beautiful things are love and death.”* He goes on to observe to himself, locked in this bizarre, quiet room, “It looked more like a chapel than a bedroom. More like a mortuary chapel, it suddenly struck me; with a sequence of corpses at rest and beflowered on the bierlike bed behind the door” (p.22).

This bizzarerie worsens when the madame invites him to touch and examine the clothes of Chrysothème, giving commands such as, “Lift the dress to your face,” “Kneel on it. Tread on it,” and “Why don’t you kiss it?” The painter obeys every one, and the madame notes, “You could almost wear it yourself…you like wearing blue and you are thin enough” (p.23).

This psycho-sexual, fetishistic examination of Chrysothème’s apparel culminates when Madame A invites him to open a chest full of her lingerie and underwear. Again, compelled both by the madame and by his own urges, he obeys, saying that “the scent was intoxicating in itself” (p.24). Lost in this reverie, he is unaware of the passing of time until he realizes he is cold and has lost his sense of smell. Then:

“And at that moment, for the first time, I really apprehended the one picture, which hung above the wide bed in the corner. Despite the bad light, it seemed familiar. I went over to it and, putting one knee on the bed, leaned toward it. Now I was certain. The picture was by me” (p.25).

At this point the unfortunate painter has had enough, and after the madame vituperates whoever it was that painted such dreck, he flees. Out in the hall he finds, “squatted on the single golden light that hung by a golden chain from the golden ceiling of the landing, was a tiny, fluffy animal, so very small that it might almost have been a dark furry insect with unusually distinct pale eyes” (p.25).

This provides further motivation to hightail it out of the house. On his way out, the madame follows him with a pair of scissors, imploring him to give her a lock of hair as a souvenir. He dodges her, saying good night, and steps out into the Belgium night towards the Chausee d’Ixelles.

Santiago Caruso, The Peacock Escritoire.

As if this were not an odd enough capper, Aickman finishes the story in this way:

“Within twenty-four hours I perceived clearly enough that there could have been no dog, no little animal squatted on the lantern, no picture over the bed, and probably no adopted daughter. That hardly needed saying. The trouble was, and is, that this obvious truth only makes things worse. Indeed, it is precisely where the real trouble begins. What is to become of me? What will happen to me next? What can I do? What am I?” (p.26).

Well, alright, Robert. Not only does he detail the anonymous painter’s erosion of faith in material reality, par for the course, but he also lists the diffuse symbols and manifestations employed throughout the tale! Of course, when the painter says himself in such a plain manner that the dog and animal and so on could not have existed, the reader should be skeptical.

Nonetheless, I suspect he is right. And this is, by the way, an interesting variation on the venerable “supernatural explained materialistically by improbable crap” ending. Rather than stating via authorial dogma that what happened is not real, Aickman delegates the messy coercion to a plebeian narrator (and not even the only cheek on the narrative throne!), thus implicitly undermining such a position. And not to mention that the “explanation” part is left out as well.

The most ready explanation for all of this is that when the painter enters the house of Madame A, he is more or less penetrating into the substance of his own consciousness, whether literally or figuratively**. I am tempted to suggest, perhaps both crassly and traditionally, that the house and its inhabitants can be broken up into the classic Freudian trinity of Ego, Super-Ego, and Id. This is a literalization of Aickman’s belief that the proper ghost story should “draw upon the unconscious mind in the manner of poetry.”

If we take this rather basic line, Madame A, with her sexual and salacious injunctions, must stand in for the Id. The long living room, as the mediator between various spaces in the house, would be the Ego, troubled by fleeting visitants from other parts. The dog and insect-animal would be errant strands of thought from the unconscious, from “the darkness outside.” What then, is the room of Chrysothème, and where does this leave the Super-ego in the traditional topographical model?

Contra to the psychoanalytic interpretation, the easiest explanation is that she is the classical, gendered artistic muse, with her clothing as the material of the sought-for, “intoxicating” ineffable. It is worth noting that the muse is still untouchable, still mediated by barriers. But what does it mean that the painter grows cold after handling the ineffable, after coming so close to touching the flesh of the muse? Does this suggest an emptiness at the heart of materialism and material reality? That it is better not to ‘know,’ the carnal sense included? In a way, Chrysothème is the meaning of the story itself. Distant, untouchable, and intoxicating, and all the more so because we know that we can never ‘see her naked.’***

So this tawdry Freudian model has collapsed, unless I make the claim that the symbolist art-pieces hold the Super-ego function of providing an authoritative model for how to “properly” engage and behave in an artistic tradition. They would stand then, in contradistinction to the unadulterated substance of inspiration, the mainlining of muse, provided by Chrysothème’s wardrobe. This would be a stretch.

So even if the ol’ Freudian interpretation doesn’t quite work, I’m still not ready to reject the interpretation that our unnamed and faintly disappointing painter has permeated the slimy membrane over his own brain-bulb. Yet as a version of the “it was all a dream” trope, this too, is faintly disappointing, isn’t it? Surely it must be grounded in some kind of reality, if for nothing else than the sake of being something more than a man walking through the “lacunous vastitude” of his own psyche.****

Let’s posit an alternative.

A theme that runs through “Ravissante” is the artist that feels alienated from her own creative processes. The painter in question feels that his work comes from “someone else.” This is the “inspiration as possession” theme, given more erotic flavoring. If this line is taken, the tale becomes somewhat meta-fictional. Our painter comes to a house that is a shadowed and fleshy ontological tunnel into his own mind. He is introduced to the source of his own inspiration (the muse, like Big Brother, can never be met directly), at which point he is possessed by this source in a rather creepy, onanistic way. But despite being a possession mediated through second-hand objects – with clothing used as prophylactics in the weirdest way ever, possibly – it is still a fertile possession. Chrysothème is not so much a succubus, drawing out energy, but rather a female incubus, supplying energy. She is an absentee incubus, but an incubus nonetheless.

So what this possession provides is artistic energy which the painter later uses to describe the possession in the narrative called “Ravissante.” Perhaps he wakes up into a “little death” because Chrysothème ran out of juice, and was finished having her way with him. Charming, indeed.

At this point I’ve run out of steam a bit, and might come back to expand on this later. I am unfamiliar with Philip Challinor’s interpretation of this story, but would love to hear his or anyone else’s thoughts, as I understand any singular take on his work is inadequate, and rightly so. As Aickman quotes Sacheverell Sitwell, “In the end it is the mystery which lasts and not the explanation.”

Meanwhile, it is October. The trees are tuberculitic, and will soon enough spit out their veined leaves like orbs of blood onto the ground, onto the wet streets and lawns. As splendid a time to read Robert Aickman as any. I recommend everyone do so.

*Robert Aickman had a collection published in 1977 titled ‘Tales of Love and Death.’

** If so, it has a strong, structural similarity to Fredric Brown’s 1960 tale, “The House,” an even more abstruse weird tale that, like “Ravissante,” is more mysterious than it is unsettling. And it is unsettling.

*** I am also not averse to the hilarious idea that Madame A is simply a dirty old lady who likes to make young men smell her underwear.

**** Phrase courtesy of Hilda Hilst.